What Is The Story Behind The Starry Night Painting?

The depiction of night in paintings is common in Western art. Paintings that feature a night scene as the theme may exist religious or history paintings, genre scenes, portraits, landscapes, or other subject types. Some artworks involve religious or fantasy topics using the quality of dim night light to create mysterious atmospheres. The source of illumination in a night scene—whether it is the moon or an artificial light source—may be depicted direct, or it may be implied by the character and coloration of the lite that reflects from the subjects depicted.

Historical overview [edit]

Commencement in the early on Renaissance, artists such as Giotto, Bosch, Uccello and others told stories with their painted works, sometimes evoking religious themes and sometimes depicting battles, myths, stories and scenes from history, using dark-time as the setting. Past the 16th and 17th centuries, painters of the late Renaissance, Mannerists, and painters from the Baroque era including El Greco, Titian, Giorgione, Caravaggio, Frans Hals, Rembrandt, Velázquez, Jusepe de Ribera frequently portrayed people and scenes in night-time settings, illustrating stories and depictions of real life.

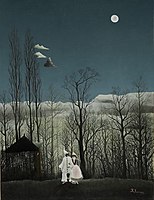

Eighteenth-century Rococo painters Antoine Watteau, François Boucher, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, and others used the dark-time theme to illustrate scenes of the imagination, oft with dramatic literary connotations, including scenes of secret liaisons and romantic relationships reminiscent of the popular 1782 book Les Liaisons dangereuses by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos. Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, used the themes of nighttime to depict illustrations of ordinary life. Poet and painter William Blake and painter Henry Fuseli used the night-time in their work as the setting for many of their most imaginative visions. The most dramatic use of the night-fourth dimension can be seen in the 1793 painting past Jacques-Louis David, chosen The Death of Marat, portraying the French revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat later on his murder by Charlotte Corday.

The night in paintings of the 19th century was used to convey a complex of diverse meanings. A mystical, religious, and sublime reverence for nature is seen in Caspar David Friedrich, Thomas Cole, Frederick Church building, Albert Bierstadt, Albert Pinkham Ryder and others, while the powerful and dramatic romanticism of Francisco Goya, Théodore Géricault, and Eugène Delacroix served as visual reportage of current events, and in the instance of Géricault revealed a scandal. Gustave Courbet, who with Honoré Daumier, Jules Breton, Jean-François Millet, and others created the Realist school, portrayed ordinary people hard at piece of work, traveling, or engrossed in their everyday lives, at night and during the day. The Impressionists and Post-Impressionists of the belatedly 19th century used the nighttime-time theme to express a multitude of emotional and aesthetic insights seen most dramatically in the paintings of Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh and others.

Symbolism [edit]

Black and grey shades often symbolize gloom, fearfulness, mystery, superstitions, evil, death, secret, sorrow. The light source in about religious paintings symbolize hope, guidance or divinity.

In fantasy paintings light could symbolize magic, like the following lines of a poem entitled The Magic: "At that place'southward magic in this evening, enshrouded in this night, hidden, like a lamp in an old human being'due south robe, there'south MAGIC."[1] : 61

History [edit]

14th century [edit]

-

-

Taddeo Gaddi, Nativity, circa 1325, Fundación Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza, Pedralbes[ii]

Gaddi, The Angelic Announcement to the Shepherds [edit]

One of the first attempts in depicting night in paintings was by Taddeo Gaddi, an Italian painter and architect.[four] : 67 Gaddi, fascinated by nocturnal lighting, depicted the event of the calorie-free in The Angelic Annunciation to the Shepherds dark scene. The fresco at Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence, Italy features an incandescent angel every bit it hovers over a shepherd.[3] : 91 Confronting the nighttime sky the brilliance of the angel's vivid glow, probable intended as "verification of the presence of God and as a metaphor for spiritual enlightenment", appears to startle the shepherd. Gaddi's utilise of monochromatic colors in and around the shepherd reveals how the colors are fabricated pale due to the remarkable illumination.[five] : 177, 179 [nb 1]

Giotto, Crucifixion [edit]

Giotto di Bondone (1266/seven–1337), Taddeo Gaddi'southward teacher and godfather,[4] : 67 [nb ii] created the fresco of Crucifixion, i of the multiple frescoes that told the story of Christ'southward life, for the Arena Chapel. He depicts Christ on a cantankerous, while the Virgin Mary is comforted by John. Kneeling at his feet is Mary Magdalene, and swirling in the sky above Jesus and the watching crowd's heads are a number of angels. Giotto depicts dark and heaven through the use of a deep blueish background in the fresco panel and use of stars in the otherwise blue ceiling.[half-dozen] : 383 [7] He was able to create depth and dimension through the use of incremental degrees of calorie-free and dark shades, the precursor to chiaroscuro. He also used calorie-free in a style to represent the divinity of people and angels from the Bible, every bit he did in other frescoes at Loonshit Chapel.[6] : 383

15th century [edit]

The Western tradition began properly in the 15th century, especially with depictions in illuminated manuscripts of the biblical night-time scenes of the Declaration to the Shepherds in the Nativity story, and the Arrest of Christ and Agony in the Garden in the Passion of Christ.

Très Riches Heures, Christ in Gethsemane [edit]

In the book of miniatures, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, the scene of Christ in Gethsemane is an apcolyptic 1 which foretells the death of Christ, through the presence of three comets in the evening sky.[9]

Uccello, Niccolò Mauruzi da Tolentino at the Battle of San Romano [edit]

-

Paolo Uccello, Niccolò Mauruzi da Tolentino at the Boxing of San Romano, National Gallery, London, The left console

-

Paolo Uccello, Niccolò Mauruzi da Tolentino unseats Bernardino della Ciarda at the Boxing of San Romano, Galleria degli Uffizi, The eye console

-

Paolo Uccello, The Counterattack of Michelotto da Cotignola at the Battle of San Romano, Musée du Louvre, Paris, The correct panel

Niccolò Mauruzi da Tolentino at the Battle of San Romano is i of a 3 painting series that captures the Battle of San Romano. The passage of time, from dawn to evening, is illustrated in the iii paintings with the initial use of pale, pastel shades and increasingly darker tones as the battle progresses.[ten] : 84, 90

Geertgen, Nascence at Night [edit]

Influenced past a vision of Saint Bridget of Sweden (1303–1373), Geertgen tot Sint Jans'southward Birth at Night depicts the infant Jesus who "radiated such an ineffable light and splendour, that the sunday was non comparable to information technology, nor did the candle that St. Joseph had put at that place, requite any light at all, the divine light totally annihilating the material light of the candle."[eleven] : 78 Strengthening the message near the baby Jesus beingness the light source, Geertgen depicts the child as the simply source of illumination for the primary scene inside the stable. Aglow are the faces of the angels, St Joseph and Virgin Mary. Although the shepherds' fire on the hill behind and the angel outside the window create a light source, information technology'southward dim in comparing to that provided past the infant kid. The abrupt contrast of the divine lite against dark is a tool used to make the scene appear more than profound for its viewers.[12] : 232 [13] London'due south National Gallery describes Geertgen'south work every bit: "one of the most engaging and convincing early treatments of the Nativity as a dark scene.[thirteen]

Annunciation to the Shepherds [edit]

In the still of the nighttime, the simply source of lite radiates in Annunciation to the Shepherds comes from an angel who has come up to tell the shepherds of the nascency of the infant Christ. The calorie-free is so brilliant that the Bethlehem shepherds must shield their eyes. Bated from the startling angel, the nocturnal painting is a pleasant, still pastoral scene with a group of angels in the distance.[14]

16th century [edit]

-

-

Albrecht Altdorfer, Dice Anbetung der Heiligen Drei Könige, c. 1530–1535, Städelsches Kunstinstitut

-

Dosso Dossi [edit]

Dosso Dossi (c. 1490 – 1542)[nb three], was an Italian Renaissance painter who belonged to the Ferrara School of Painting.[4] : 56

Albrecht Altdorfer [edit]

Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480 – 12 Feb 1538) was a German painter, engraver and architect of the Renaissance of the so-called Danube School setting biblical and historical subjects against landscape backgrounds of expressive colours.[15]

Giuseppe Cesari [edit]

Giuseppe Cesari (c. 1568 – 3 July 1640) was an Italian Mannerist painter and instructor to Caravaggio.[ commendation needed ]

17th century [edit]

-

-

-

-

-

-

Godfried Schalcken, A Man Offering a Gold Chain and Coins to a Girl Seated on a Bed, c. 1665–1670

Adam Elsheimer [edit]

Early on Baroque artist Adam Elsheimer created night scenes that were highly original. His works departed slightly[ citation needed ] from other works of the Baroque period were dramatic and abundantly detailed.[16] Bizarre paintings featured "exaggerated lighting, intense emotions, release from restraint, and fifty-fifty a kind of creative sensationalism".[17] Elsheimer'southward lighting effects in full general were very subtle, and very different from those of Caravaggio. He oft uses as many every bit five dissimilar sources of lite, and graduates the light relatively gently, with the less well-lit parts of the composition ofttimes containing important parts of information technology.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio [edit]

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was an Italian artist active betwixt 1593 and 1610. His paintings, which combine a realistic observation of the human state, both concrete and emotional, with a dramatic use of lighting, had a formative influence on the Baroque schoolhouse of painting.[6] : 298–299 [eighteen] Caravaggio's novelty was a radical naturalism that combined close physical ascertainment with a dramatic, even theatrical, use of chiaroscuro. This came to be known as Tenebrism, the shift from light to night with trivial intermediate value.[half-dozen] : 299 [xix]

Georges de La Tour [edit]

Georges de La Bout was a French Baroque painter who painted mostly religious chiaroscuro scenes lit by candlelight, which were more than developed than his artistic predecessors, yet lacked dramatic effects of Caravaggio. He created some of the nigh arresting works in this genre, portraying a wide range of scenes by candlelight from bill of fare games to New Testament narratives.[xx]

Aert van der Neer [edit]

The Dutch Gilt Historic period painter Aert van der Neer was a landscape painter, specializing in small night scenes lit only past moonlight and fires, and snowy winter landscapes, both often looking down a canal or river.

Anthony van Dyck [edit]

Anthony van Dyck (22 March 1599 – nine December 1641) was a Flemish Baroque artist and leading courtroom painter in England.

18th century [edit]

Joseph Turner [edit]

Joseph Mallord William Turner (23 Apr 1775 – 19 December 1851) was an English Romantic mural painter,[21] who is ordinarily known as "the painter of light".[22]

Joseph Vernet [edit]

Claude-Joseph Vernet (14 August 1714 – 3 December 1789) was a French painter whose landscapes, including those of moonlights were pop with English aristocrats. His The Port of Rochefort (1763, Musée national de la Marine) is specially notable; in the slice Vernet is able to attain, according to art historian Michael Levey, one of his most 'crystalline and atmospherically sensitive skies'.[23]

Joseph Wright [edit]

Joseph Wright of Derby (3 September 1734 – 29 August 1797) was an English language landscape and portrait painter who is notable for his utilise of Chiaroscuro effect, which emphasises the contrast of light and dark, and for his paintings of candle-lit subjects. Wright is seen at his all-time in his candlelit subjects. The Three Gentlemen observing the 'Gladiator' (1765). A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery shows an early mechanism for demonstrating the movement of the planets around the lord's day. An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768) shows people gathered round observing an early on experiment into the nature of air and its ability to support life.

These factual paintings are considered to have metaphorical meaning also, the bursting into light of the phosphorus in forepart of a praying figure signifying the problematic transition from faith to scientific understanding and enlightenment, and the various expressions on the figures effectually the bird in the air pump indicating concern over the possible inhumanity of the coming historic period of scientific discipline.[24]

19th century [edit]

Théodore Géricault [edit]

Théodore Géricault (26 September 1791 – 26 January 1824) was an influential French artist and one of the pioneers of the Romantic movement.

Atkinson Grimshaw [edit]

Atkinson Grimshaw (6 September 1836 – thirteen October 1893) was a Victorian-era artist[26] : 173 known for his urban center night-scenes and landscapes.[27] [28] His careful painting and skill in lighting effects meant that he captured both the appearance and the mood of a scene in minute detail. His "paintings of dampened gas-lit streets and misty waterfronts conveyed an eerie warmth besides equally alienation in the urban scene."[29] : 99

On Hampstead Hill is considered one of Grimshaw'south finest works, exemplifying his skill with a variety of calorie-free sources, in capturing the mood of the passing of twilight into dark. In his later career his urban scenes under twilight or yellow streetlighting were popular with his heart-form patrons.[30] : 154

In the 1880s, Grimshaw maintained a London studio in Chelsea, not far from the studio of James Abbott McNeill Whistler. After visiting Grimshaw, Whistler remarked that "I considered myself the inventor of Nocturnes until I saw Grimmy'due south moonlit pictures."[31] : 112 Unlike Whistler'due south Impressionistic nighttime scenes Grimshaw worked in a realistic vein: "sharply focused, near photographic," his pictures innovated in applying the tradition of rural moonlight images to the Victorian metropolis, recording "the rain and mist, the puddles and smoky fog of late Victorian industrial England with great verse."[31] : 112–113

Petrus van Schendel [edit]

Petrus van Schendel (1806–1870) was a Dutch Romantic painter,[32] etcher and draughtsman. Van Schendel specialised in nocturnal Dutch market scenes, exploring the effects the soft light had upon his subjects, as a result he was named Monsieur Chandelle by the French. Van Schendel was inspired by these famous forebears, but brought a unique nineteenth century mood to his nighttime scenes. He eloquently captured the mysterious world of city markets illuminated by lamps and moonlight before the dawn.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler [edit]

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (11 July 1834 – 17 July 1903) was an American-built-in, British-based artist.[33] : 50

Whistler'southward sick-brash journeying in 1866 to Valparaíso, Chile,[33] : 141 resulted in Whistler's first three nocturnal paintings—which he termed "moonlights" and after re-titled as "nocturnes"—night scenes of the harbor painted with a blueish or light green palette. Afterwards in London, he painted several more nocturnes over the next ten years, many of the River Thames and of Cremorne Gardens, a pleasance park famous for its frequent fireworks displays, which presented a novel challenge to paint. In his maritime nocturnes, Whistler used highly thinned paint as a basis with lightly flicked color to suggest ships, lights, and shore line.[6] : 368 [34] : 30 Some of the Thames paintings likewise evidence compositional and thematic similarities with the Japanese prints of Hiroshige.[33] : 187

In 1877 Whistler sued the art critic John Ruskin for libel after the critic condemned his painting Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket. Ruskin accused Whistler of "asking ii hundred guineas for throwing a pot of paint in the public's face."[35] Whistler won the conform, only was awarded 1 farthing for damages.[36] The cost of the example bankrupted him. It has been suggested John Ruskin suffered from CADASIL and the visual disturbances this condition caused him might accept been a factor in his irritation at this particular painting.[37] Whistler published his account of the trial in the pamphlet Whistler 5. Ruskin: Fine art and Art Critics, included in his later The Gentle Fine art of Making Enemies (1890).

20th century [edit]

Famous examples [edit]

The Night Watch, Rembrandt van Rijn [edit]

The Night Lookout or The Shooting Company of Frans Banning Cocq by Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn is one of the nearly famous paintings in the world.[ citation needed ] One of its key elements is the constructive use of low-cal and shadow (chiaroscuro).[38] : 61, 65 Made in 1642, it depicts the eponymous company moving out, led by Captain Frans Banning Cocq (dressed in blackness, with a ruby-red sash) and his lieutenant, Willem van Ruytenburch (dressed in yellow, with a white sash).[ commendation needed ] With effective apply of sunlight and shade, Rembrandt leads the middle to the 3 near of import characters amongst the crowd, the two gentlemen in the centre (from whom the painting gets its original title), and the small daughter in the centre left background.[38] : 65

For much of its existence, the painting was coated with a dark varnish which gave the incorrect impression that information technology depicted a night scene, leading to the name by which information technology is now commonly known. The heavy varnish was merely discovered in the 1940s and restoration began after 1975.[39] : 224–225

The Third of May 1808, Francisco Goya [edit]

The Tertiary of May 1808 by Spanish painter Francisco Goya commemorates Castilian resistance to Napoleon's armies during the occupation of 1808 in the Peninsular State of war.[40] : 109 The painting's content, presentation, and emotional strength secure its condition as a groundbreaking, archetypal image of the horrors of war. Although it draws on many sources from both high and pop art, The Third of May 1808 marks a clear break from convention. Diverging from the traditions of Christian fine art and traditional depictions of war, it has no singled-out precedent, and is acknowledged every bit one of the kickoff paintings of the modern era.[40] : 116–127 According to the art historian Kenneth Clark, The Tertiary of May 1808 is "the first great picture which can be called revolutionary in every sense of the discussion, in style, in subject, and in intention".[41] : 130.

It is set in the early hours of the morning following the uprising[39] : 363 and centers on two masses of men: i a rigidly poised firing squad, the other a disorganized grouping of captives held at gun point. Executioners and victims face each other abruptly across a narrow space; according to Kenneth Clark, "past a stroke of genius [Goya] has contrasted the vehement repetition of the soldiers' attitudes and the steely line of their rifles, with the aging irregularity of their target."[41] : 127 A foursquare lantern situated on the ground between the ii groups throws a dramatic lite on the scene. The brightest illumination falls on the huddled victims to the left, whose numbers include a monk or friar in prayer.[42] : 297 The central figure is the brilliantly lit human kneeling amid the bloodied corpses of those already executed, his arms flung wide in either appeal or defiance.[twoscore] : 116

The painting is structurally and thematically tied to traditions of martyrdom in Christian art, equally exemplified in the dramatic use of chiaroscuro, and the appeal to life juxtaposed with the inevitability of imminent execution.[40] : 121 However, Goya's painting departs from this tradition. Works that depicted violence, such every bit those by Jusepe de Ribera, feature an aesthetic technique and harmonious composition which anticipate the "crown of martyrdom" for the victim.[40] : 118

The lantern every bit a source of illumination in fine art was widely used by Baroque artists, and perfected by Caravaggio.[40] : 119 Traditionally a dramatic lite source and the resultant chiaroscuro were used as metaphors for the presence of God. Illumination by torch or candlelight took on religious connotations; but in The Third of May the lantern manifests no such phenomenon. Rather, information technology affords low-cal but so that the firing squad may consummate its grim work, and provides a stark illumination so that the viewer may carry witness to wanton violence. The traditional role of lite in art as a conduit for the spiritual has been subverted.[40] : 119

The Starry Nighttime, Vincent van Gogh [edit]

The Starry Nighttime, made by Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh, depicts his retention of the view outside his sanitorium room window at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (located in southern French republic) at night.[43] : 225 Although Van Gogh was not very happy with the painting,[44] art historian Joachim Pissarro cites The Starry Night as an exemplar of the artist'southward fascination with the nocturnal.[45] Ane of Van Gogh's most popular pieces, the painting is widely hailed every bit his magnum opus.[43] : 225

Nighthawks, Edward Hopper [edit]

Edward Hopper had a lifelong interest in capturing the effect of calorie-free on the objects it touched, including the nighttime result of bogus, human-fabricated light spilling out of windows, doorways and porches. Nighthawks was probably Hopper's almost aggressive essay in capturing the dark-time effects of man-fabricated light. For one thing, the diner's plate-glass windows cause significant light to spill out onto the sidewalk and the brownstones on the far side of the street. Besides, interior light comes from more than a unmarried lightbulb, with the result that multiple shadows are bandage, and some spots are brighter than others as a issue of being lit from more than i angle. Across the street, the line of shadow caused by the upper edge of the diner window is clearly visible towards the top of the painting. These windows, and the ones below them equally well, are partly lit past an unseen streetlight, which projects its own mix of light and shadow. As a final note, the bright interior light causes some of the surfaces inside the diner to be reflective. This is clearest in the case of the right-mitt border of the rear window, which reflects a vertical yellowish ring of interior wall, but fainter reflections tin can as well exist made out, in the counter-top, of three of the diner's occupants. None of these reflections would be visible in daylight.[ citation needed ]

The Empire of Low-cal, René Magritte [edit]

In his 1950 painting The Empire of Light, René Magritte (1898–1967),[46] explores the illusion of night and day, and the paradox of fourth dimension and light. On the tiptop one-half of his canvas Magritte paints a clear bluish sky and white clouds that radiate bright daytime; while on the bottom half of his canvas below the heaven, he paints a street, sidewalk, trees and houses all steeped in the darkness of night. The darkened trees and darkened houses appear to be in night shadows, in the centre of the nighttime; and the sidewalk streetlight is on to guide the way. Some of the questions implied past these pictures include is it night-time? is it daytime? or is information technology just a painting? The Empire of Light is i of a series of paintings that René Magritte painted betwixt 1950 and 1954 that explores his surrealist insight into illusion and reality, using dark and day as his field of study.[47] [46]

Gallery [edit]

-

-

-

-

-

Pedro Américo, The Dark Escorted by the Geniuses of Love and Study, 1886

See likewise [edit]

- Black Paintings

- Nocturne (painting)

- History of painting

- Night photography

Notes [edit]

- ^ A pupil and godson of Giotto di Bondone, Gaddi was influenced by Giotti's exploration away from traditional Medieval artistic works towards evolution of solid three-dimensional characters using contrasting night and light shades to suggest depth and shape. The technique was a precursor to chiaroscuro.[4] : 67 [half-dozen] : 209 Gaddi may have sought to leverage this technique to its all-time reward after having accepted the prominent commission for the church fresco early in his career to impress the public and his patrons.[v] : 177, 179 Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum[A] notes that: "This ensemble [The Celestial Declaration to the Shepherds] is noted for its dynamism, pronounced foreshortening, dramatic effects of low-cal and interest in narrative."[2] This is evidenced by the touch on Gaddi'due south piece of work had on successive church murals, such as the nearby Rinuccini Chapel'south mural made about 40 years later.[v] : 177

- ^ Giotto was an Italian painter in the belatedly Eye Ages and generally considered a central correspondent to the Italian Renaissance. In his day medieval paintings depicted flat, relatively unemotional people. Giotto, revolutionary for the 13th century, portrayed natural, three-dimensional people.[half dozen] [7]

- ^ The 2003 Columbia Encyclopedia cites birthdate as c. 1479. The Getty Museum (which owns some of Dossi's works), Britannica, Encarta, and the monograph below cite birthdate as c. 1490.

- ^ Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum has in its collection Taddeo Gaddi'south Birth which was made about 1325.

References [edit]

- ^ Favorite, 1991.

- ^ a b Taddeo Gaddi, Biography. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ a b Paoletti and Radke, 2005.

- ^ a b c d Farquhar, 1855.

- ^ a b c Norman, 1995.

- ^ a b c d e f chiliad Gardner and Kleiner, 2009.

- ^ a b "The Life of Christ: The Story of Christ: The noblest paintings of the Savior'southward life were done by Giotto for a chapel in Italian republic." Life Magazine, Fourth dimension Inc., 27 December 1948. 25: 26. pp. 52, 53, 57. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ^ The Battle of San Romano. National Gallery, London. Retrieved 28 Baronial 2012.

- ^ Scheckner, p. 238.

- ^ Duffy, 1998.

- ^ Schiller, including quotation.

- ^ Campbell, 1998.

- ^ a b The Nativity at Nighttime. The National Gallery, London. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ The Declaration to the Shepherds. J. Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ Murray, Linda (1967). The Loftier Renaissance and Mannerism. London, England: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 246–247. ISBN0-500-20162-5.

- ^ Claude V. Palisca, "Bizarre". The New Grove Lexicon of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001).

- ^ Hunt, Martin, Rosenwein, and Smith (2010). The Making of the West (third ed.). Boston: Bedford/ St. Martin's. pp. 469

- ^ "ULAN Total Record Display (Getty Research)". www.getty.edu.

- ^ Quoted in Gilles Lambert, "Caravaggio", p.8.

- ^ Edgeless.

- ^ Lacayo, Richard, The Sunshine Boy, Time Magazine, 11 October 2007.

- ^ Turner, Joseph Mallord William Archived 25 May 2010 at the Wayback Car National Gallery, London

- ^ Levey.

- ^ Baird, Olga; Malcolm Dick. "Joseph Wright of Derby: Art, the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution". Archived from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- ^ Jimloy.com

- ^ Wood, 1999.

- ^ Robertson, 1996.

- ^ H. J. Dyos, 1973.

- ^ Waller, 1983.

- ^ Steer.

- ^ a b Lambourne, 1999.

- ^ WG Flippo. (1981). Lexicon of the Belgian Romantic Painters, Antwerp.

- ^ a b c Anderson and Koval, 2002.

- ^ Peters, 1998.

- ^ From the Tate, retrieved 12 April 2009

- ^ Whistler, James Abbott McNeill. WebMuseumn, Paris

- ^ Kempster PA, Alty JE. (2008). John Ruskin's relapsing encephalopathy [ dead link ] . Encephalon. Sep;131(Pt 9):2520-5. doi:10.1093/brain/awn019 PMID 18287121

- ^ a b Boka and Courteau, 1994.

- ^ a b Hagen and Hagen, 2003.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g Licht, 1979.

- ^ a b Clark, 1968.

- ^ Boime, 1990.

- ^ a b Zara, 2012.

- ^ Van Gogh, Vincent. (writer). Harrison, Robert. (ed.) (19 September 1889) Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written in Saint-Rémy. Translated by Mrs. Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, number 607. Webexhibits.org Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Vogel, Carol. (thirteen June 2008). Nytimes.com Darkness Was Muse for a Master of Light. The New York Times. Retrieved 24 Baronial 2012.

- ^ a b "The Drove | MoMA". The Museum of Mod Fine art.

- ^ "Guggenheim Museum".

Sources [edit]

- Anderson, Ronald and Anne Koval. (2002). James McNeill Whistler: Across the Myth. Da Capo Printing. ISBN 0-7867-1032-ii. (Note: need to verify this was the edition used.)

- Boime, Albert. (1990). Art in an Age of Bonapartism, 1800–1815. The University of Chicago Printing. ISBN 0-226-06335-6.

- Edgeless, Anthony. (1999) [1953]. Art and Architecture in France, 1500–1700. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07748-3.

- Boka, Georges and Bernard Courteau. (1994). Rembrandt's Nightwatch : The Mystery Revealed. Georges Boka Editeur. ISBN two-920217-41-0.

- Campbell, Lorne, National Gallery Catalogues (new serial). (1998). The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings. National Gallery Publications. ISBN 1-85709-171-X.

- Clark, Kenneth. (1968). Looking at Pictures. Buoy Press. ISBN 0-8070-6689-3. (found on Artchive)

- Duffy, Jean H. (1998). Reading Betwixt the Lines: Claude Simon and the Visual Arts. Volume 2 of Modernistic French Writers. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-851-0.

- Dyos, H. J. and Michael Wolff (eds.) (1999) [1973]. The Victorian City: Images and Realities, 2 Volumes. Psychology Printing. ISBN 0-415-19323-0.

- Farquhar, Maria. (1855). Biographical itemize of the principal Italian painters: with a table of the gimmicky schools of Italian republic. Designed as a hand-volume to the picture gallery. J. Murray.

- Favorite, Malaika. (1991). Illuminated Manuscript: Poems and Prints. New Orleans Poetry Journal. Journal Press Books: Louisiana Legacy. ISBN 0-938498-09-6.

- Freedberg, Sidney J. (1971). Painting in Italy, 1500–1600, first edition. The Pelican History of Art. Harmondsworth and Baltimore: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-056035-1.

- Gardner, Helen and Fred South. Kleiner. (2009). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Concise Global History. (second edition). Cengage Learning. ISBN 0-495-50346-0.

- Hagen, Rose-Marie and Hagen, Rainer. (28 February 2003.) What Bully Paintings Say. Taschen. ISBN three-8228-2100-4

- Henderson, Andrea and Vincent Katz. (2008). Picturing New York: The Art of Yvonne Jacquette and Rudy Burckhardt. Museum of the City of New York, Correspondent. Bunker Hill Publishing. ISBN i-59373-065-9.

- Licht, Fred. (1979). Goya: The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art. Universe Books. ISBN 0-87663-294-0

- Lambourne, Lionel. (1999). Victorian Painting. London: Phaidon Printing.

- Norman, Diana. (1995). Siena, Florence and Padua: Art, Society and Religion 1280–1400, Volume II. Yale University Printing. ISBN 0-300-06127-7.

- Paoletti, John T. and Gary M. Radke. (2005). Art in Renaissance Italy, 3rd edition. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN one-85669-439-9.

- Peters, Lisa N. (1998). James McNeil Whistler. Todtri. ISBN 1-880908-70-0.

- Robertson, Alexander. (1996). Atkinson Grimshaw. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-2525-5.

- Schechner, Sara. (1999). Comets, Popular Culture, and the Birth of Mod Cosmology. Princeton Academy Press. ISBN 0-691-00925-two.

- Schiller, Gertrud. (1971). Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I. (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London. ISBN 0-85331-270-2.

- Steer, Isabella. (2002). The History of British Fine art. Bath: Parragon. ISBN 0-7525-7602-X

- Waller, Philip J. (1983). Boondocks, City, and Nation. Oxford: Oxford University Printing.

- Wood, Christopher. (1999). Victorian Painting. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

- Zara, Christopher. (2012). Tortured Artists: From Picasso and Monroe to Warhol and Winehouse, the Twisted Secrets of the World's Most Creative Minds. Adams Media. ISBN 1-4405-3003-3.

- Possible sources

- Jethani, S (2009). The Divine Commodity: Discovering a Religion Beyond Consumer Christianity. 1000 Rapids, MI: Zondervan (eBook). ISBN 978-0-310-57422-4.

- Selz, Peter. (1974). German Expressionist Painting. Academy of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02515-6.

- Suckale, Robert and Manfred Wundram, Andreas Prater, Hermann Bauer, Eva-Gesine Baur. (2002). Masterpieces of Western Fine art: A History of Fine art in 900 Individual Studies from the Gothic to the Present Twenty-four hour period. Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-1825-9.

- Taylor, William Edward and Harriet Garcia Warkel, Margaret Taylor Burroughs. (authors) Indianapolis Museum of Fine art. (ed.) (1996). A Shared Heritage: Fine art by Four African Americans. Undiana University Press. ISBN 0-936260-62-9.

- Van de Wetering, Ernst. (2002). Rembrandt: The Painter at Piece of work. Rembrandt Serial. Amsterdam Academy Press. ISBN 90-5356-239-7.

- Van Gogh, Vincent and Sjraar van Heugten, Joachim Pissarro, Chris Stolwijk. (2008). Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night The Museum of Modern Fine art. ISBN 0-87070-737-X.

Farther reading [edit]

- Anderson, Nancy. (2003). Frederic Remington: The Color of Night. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11554-0.

- Denham, Robert D. (2010). Poets on Paintings: A Bibliography. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-4725-7.

- Elkins, James (2004). Pictures & Tears: A History of People Who Have Cried in Front end of Paintings. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97053-nine.

- Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent van Gogh. K Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- Greenaway, Peter. (2006). Nightwatching: a view of Rembrandt's The Night Watch. Veenman. ISBN 90-8690-013-5.

- Katz, Alex and Donald Burton Kuspit. (1991). Nighttime paintings. H.N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-3502-3.

- "The Life of Christ: The Story of Christ: The noblest paintings of the Saviour's life were done by Giotto for a chapel in Italian republic." Life Magazine, Fourth dimension, Inc. 27 Dec 1948. 25: 26. p. 32–57. ISSN 0024-3019.

- MacDonald, Margaret F. (2001). Palaces in the Night: Whistler in Venice. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23049-3.

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Hokusai Katsushika; Kojiro Tomita. (1957). Twenty-four hours and nighttime in the 4 seasons. Volume 14 of Picture book serial. Museum of Fine Arts.

- Nasgaard, Roald. (2007). Abstract Painting in Canada. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 1-55365-394-seven.

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Night_in_paintings_(Western_art)

Posted by: richmondsperwit.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Story Behind The Starry Night Painting?"

Post a Comment